Earlier this year I visited MONA in Hobart, and more recently MONAS (Monumen Nasional) in Jakarta – very different, culturally, but similar in the way they both tell a story about our times through the medium of art. Both feature sculpture but, again, like chalk and cheese in execution and intent.

Earlier this year I visited MONA in Hobart, and more recently MONAS (Monumen Nasional) in Jakarta – very different, culturally, but similar in the way they both tell a story about our times through the medium of art. Both feature sculpture but, again, like chalk and cheese in execution and intent.

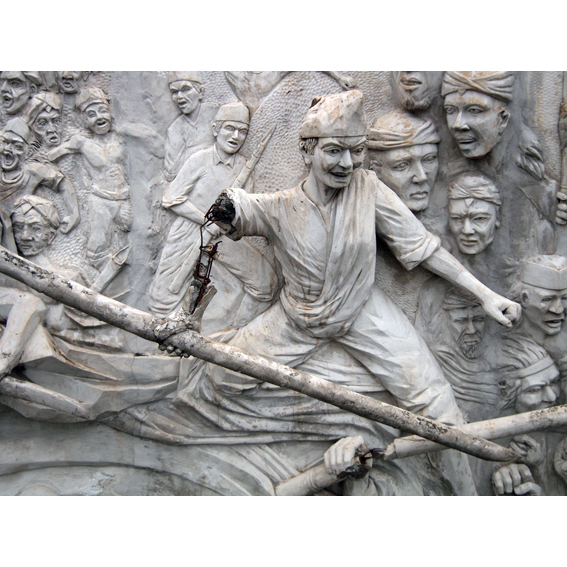

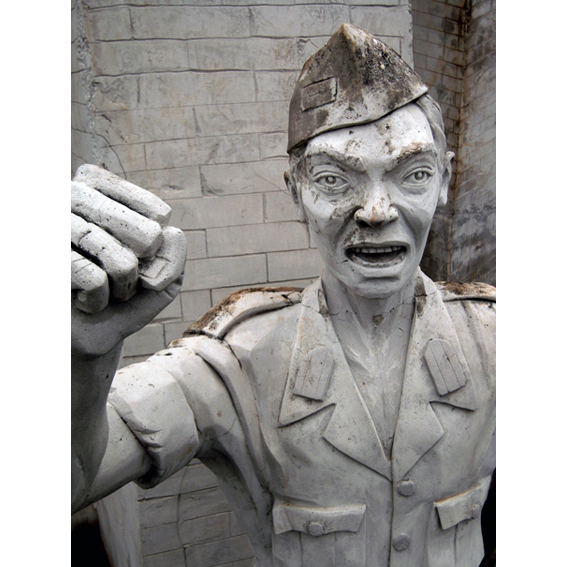

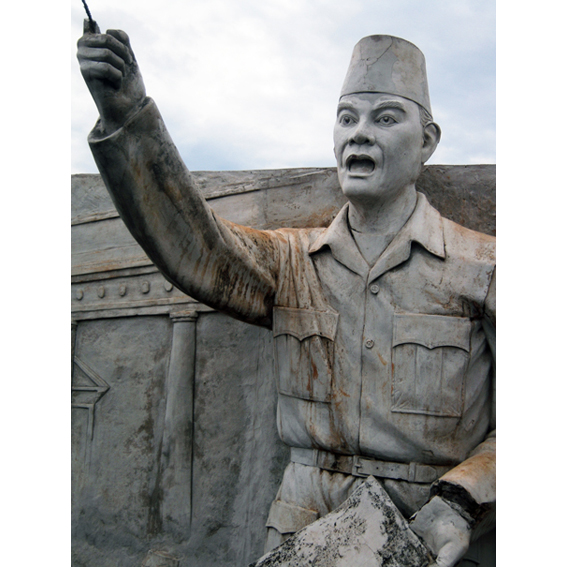

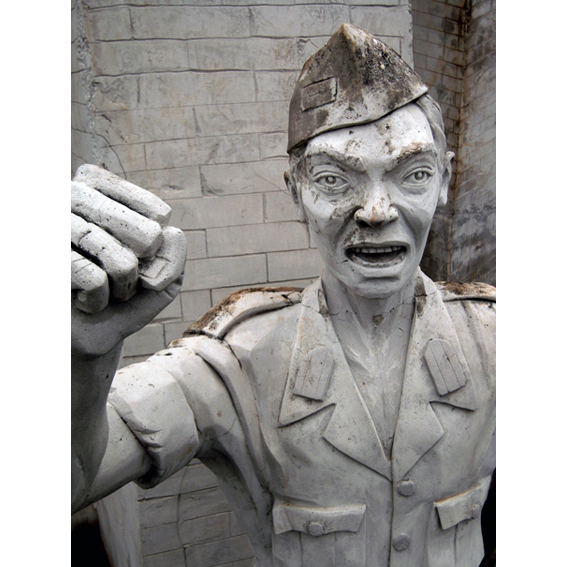

I was intrigued by these concrete reliefs that surround the base of the MONAS tower telling the story of Indonesia’s struggle for independence and the birth of a nation. They’re reminiscent of Soviet-era public works of art designed to inspire the masses and promulgate a specific version of history and a political narrative. That’s appropriate in a way, given the close relationship that Indonesia had with both the Soviet Union and China during the sixties.

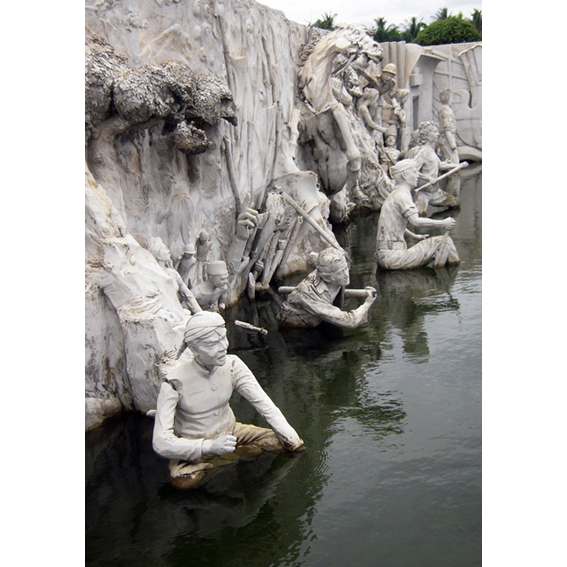

Today, the concrete reliefs are looking a trifle sad and woebegone. The concrete is cracked and broken. The figures that were once intended to inspire national pride are now mildewed and stained; many of them are standing in a half-drained pool of stagnant water. Such are the effects of time and neglect which often work to defy Man’s best efforts to write his own history.

The passing of the years and exposure to the elements has had the effect of imbuing these figures, which were originally fashioned with certain bombast and belligerence (so many open, shouting mouths), with a definite pathos. It’s hard to look intimidating or resolute when your arm is hanging off or there’s mould growing on your head. One of the figures, which I assume is Sukarno himself, has lost the tip of his finger so that now instead of looking defiantly into the future, his face is one of shock and amazement at the indignity of his digit. If he were still alive today, he might feel the same about what has happened to his statue and, indeed, his country.

One of the most poignant, too, is the elephant who looks decidedly distressed at discovering his trunk so twisted and broken.

Some of the other effects are unintentionally comic or simply bemusing. The figure of the artist, for instance, with his brushes, palette and cool beret references a decidedly Western image of the Artist, a Van Gogh-type figure. The panel on modern medicine features a one-legged invalid who seems to be in considerable pain despite the presence of two doctors, while the image behind of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, often used as a symbol for medicine, has had a fig leaf tastefully added. In contrast to the da Vinci drawing, too, the arms of the figure are lowered, which rather defeats the point of demonstrating the superimposition of two figures in a circle and square. Maybe there wasn’t enough room.

Even more incongruous though is the contrast between these figures and the modern Jakarta which surrounds them with its gleaming malls packed with the latest Western luxury goods and trinkets. Maybe that’s the source of their collective outrage and anger, voiceless and frozen in time, directed not against the imperialist overlords of yesteryear but rather at the rampant consumerism of modern Indonesia.